Disrupting the Normal Flow

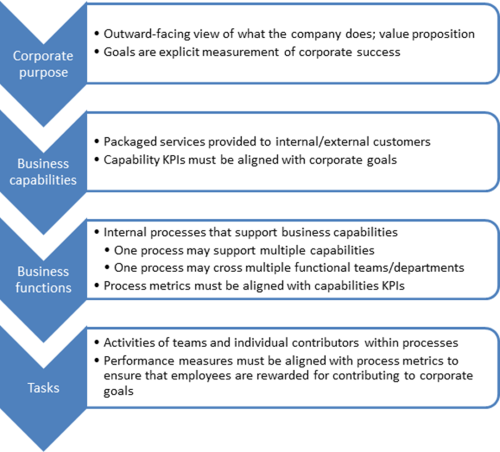

6th of September 2019Corporate Strategy is the starting point for all work that goes on in organizations. This direction set out by the highest echelons of management drives what value an organization wants to offer its customers, and how it goes about creating it. There are numerous corporate goals: revenue growth, competitive differentiation, product agility, customer retention, market share increase, and so on. From these strategic goals come flowing goals and objectives to the lower echelons, who in turn will translate them into initiatives to achieve these objectives. These are some of the basics set out by Kaplan and Norton in their seminal work “The Balanced Scorecard” way back near the end of the previous century. Sandy Kemsley, one of the leading business process management gurus, made a nice diagram (see below) of these trickle-down goals towards initiatives cycle in her blog recently.

This flow from strategy to execution can meet with many monkey wrenches being thrown in its wheels, necessitating a rethinking of how to tackle your day-to-day business. Such disruptions can come through many different channels. Typically, these channels are divided into external factors (such as new competitors, vendor/supplier switches, industry changes or the like) and internal factors (such as company restructuring through mergers and acquisitions, senior leadership changes, employee dissatisfaction…).

Or these changes can be started because of the realities on an operational level. At this level business managers are faced with stipulations about operating profitability, service times, and operational scalability, that might necessitate a change. When reviewing Roger Tregear’s book “Reimagining Management”, I came across his description of several drivers for change that might influence processes as executions of corporate strategy. These changes are triggered from within as a result of the following drivers:

- Impact-Driven Triggers: process execution-level impact of failing target value creation.

- Innovation-Driven Triggers: process execution-level impact of new ideas and technologies.

- Change-Driven Triggers: process execution-level impact of changes in the organizational ecosystem.

- Performance-Driven Triggers: process execution-level impact of measured performance issues.

Wherever these disruptions might come from, they will have an impact on the architectures that have been made for past and planned initiatives within the organization, and thus should be on the radar of any architect tasked with designing them. Knowing where they can come from is half the battle, as it allows us to incorporate provisions aimed at designing our architectures with a level of adaptability to address these types of changes. So, here is a quick list of the different avenues from which they can enter the corporate reality:

Disruption from Within

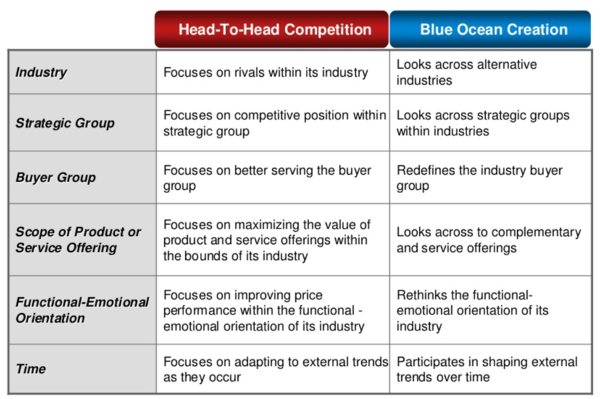

One of the easiest disruptions to imagine will be when corporate strategy changes because of decisions taken on the strategic management level. These decisions to change gears can come about in different ways. Where I mentioned internal factors earlier such as mergers/acquisitions or leadership changes, these can be considered as involuntary disruptions from within. Another disruption flavor might be of the voluntary/planned variety. When a market is nearly or completely saturated with existing products/services, it is economy of scale, reputation and size of the organization that are the deciding factors on market dominancy. In such a market environment, there is no clear road to improving the organization’s status within the market through conventional strategies. A blue ocean strategy could be just the thing to disrupt not only your own organization, but the entire market segment your organization is interested in.

The term “Blue Ocean” as opposed to a “Red Ocean” was coined by W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne in their book "Blue Ocean Strategy" (Harvard Business Review Press 20050). With Red Ocean being the term for a market where businesses are viciously fighting against each other for a share of that marketplace (blood in the water, coloring it red), and Blue Ocean being the term for markets that is relatively new and thus relatively free from competitors. Depending on which marketplace the enterprise inhabits, the focus of the business strategy takes on a different set nuances, as indicated by the six paths of the Blue Ocean Strategy. The textbook example of a Blue Ocean strategy is the “Cirque du Soleil” product which revolutionized a stale circus market when it came to be.

Disruption by Customers

Professor Thales S. Teixeira at the Harvard Business School correctly assesses in a Harvard Business Review article recently that for most organizations the disruption that happens the most frequently is somewhat of a blind spot. These are the disruptions caused by your customer base. Since customers decide which products are successful in the market, and which new products are either accepted or rejected, it is only natural that corporate strategy should be driven mostly by their needs and wants.

These needs and wants also tend to be more fragmented than they are given credit for. Where a company might assume they are selling a product as a whole, it is actually corresponding to a composite of what the consumer is looking for. For example, a smart phone might look like it is a single product, but in the mind of the customer it is a device that meet his or her needs to contact other people through a variety of channels (telephone, Whatsapp, text messages…) but also a decide to pass the time playing games, listen to music, browse the web… At any time, any of these needs might become serviced by another device, decreasing the number of smartphones being sold. As stated by Professor Teixeira, this is why in the current market startup companies usually don’t steal away customer segments from established companies, but rather steal away customer activities.

Traditional companies are always on the lookout for synergies in production processes in order to expand their portfolio of services and products. It significantly reduces the threat of entry (one of the five forces of Porter) into a new market segment and allows for a transition into a more diversified organization still managed by an overarching strategic vision and produced by similar operational processes. This type of synergy also happens at the customer-side. By applying a coupling of the consumer activities in products or services from a single company, or by creating new products/services that have a synergy with your existing ones, it will become easier, cheaper, faster, … for your customers to stay with you rather than switching for one of his activities to a competitor. And keeping up with these synergies will result in a healthier bottom line.

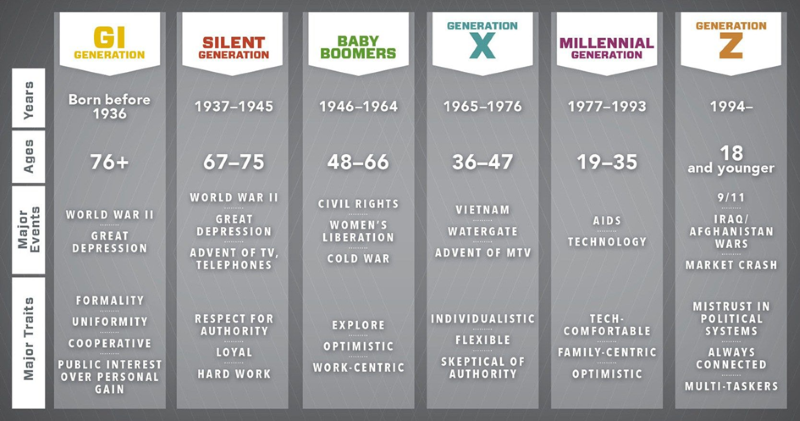

Next to shifts in needs and wants of customers about the market segment products the organization is aiming for, there are also shifts in needs and wants brought about by the overarching traits for the generations to which your customers belong. Even though these are more generic in nature, and cannot be universally applied to each individual customer, they nonetheless put your customer base in a certain mindset. Looking at the different generations that still have a significant presence, the diagram below shows for each of them their more apparent traits and by which events in their lifespan they were most affected.

As a small side note: Simon Sinek did an interview for Inside Quest back in December 2016 about what he believes are the predominant traits that govern the work life of Millenials. What he had to say might give some insights on how their needs and wants are determined. Not saying that I agree with all of his conclusions, but I do share some of the observations he is making about this age group. The traits he lists are similar to the ones in the overview, with the addition of a form of impatience governing that generation’s experiences. For example, he lists the generation as being spoiled in the way of instant acquisition. Want a specific song, Spotify will immediately give it to you, want a series, same with Netflix. This habit forces companies to heavily invest in reducing time-to-market to cater to this consumer base, as they will not wait for your product to be ready in a few months or even days.

Disruption by Technology

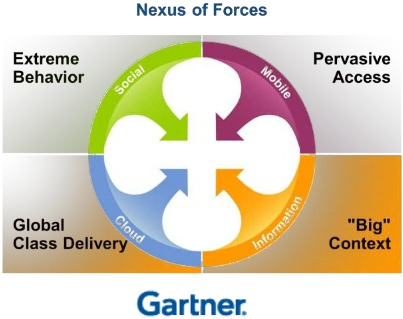

New technologies have always disrupted whole markets and even global market systems. The first viable forms of automation caused the Industrial Revolution around the mid-18th century, and the pace of technological innovations creating new rules for their respective markets hasn’t slowed down since then. When we look at IT innovations that disrupts markets even on a global scale, they were waiting for the mass adoption of the internet. Where previously IT components would act more as a support to existing processes, these new technologies would cause the rethinking of how organizations do business. The first time I came to this insight coincided with the period Gartner launched their Nexus of Forces concept.

The idea of the Nexus of Forces was the reinforcing nature of 4 emerging technologies. The centralizing piece was information and its vast volume increase. With the emergence of Big Data and the analytical models and techniques that followed it its wake, a foundation is presented for new value creation that can be carried out on new platforms such as Mobile and Social channels. The Cloud infrastructure provides a delivery method that can harmonize the other Forces. Now that we are 7 years later, all of these predicted disruptions have come to pass and each of these technologies has found a home in mainstream corporate strategic initiatives.

Evidently, Gartner hasn’t rested on its laurels, and has been releasing a yearly revision of disruptive technologies to keep up with current market affairs. There are a lot more than 4 technology trends competing in the current landscape, so Gartner divides all of these technologies into three types with some of them falling in multiple categories:

- Intelligent: Innovations that are powered or influenced by the arrival of artificial intelligence in our daily lives. Examples of these technologies are Autonomous Things (such as self-managing drones) or augmented analytics such as machine and deep learning.

- Digital: Innovations that intertwine the physical and the digital world to create an immersive experience. Examples are Immersive Experience such as Augmented Reality and Empowered Edge Computing.

- Mesh: Innovations that provide or interact with the expanding set of connections between people, businesses, devices, services, content… Examples are blockchain and smart spaces.

Disruption by Neglect

To me, it seems there are two types of neglect: involuntary and willful. Involuntary neglect is when an organization fails to recognize that any process left alone sufficiently long will inevitably turn less effective and efficient, increasing its technical debt. Marilyn Strathern, renowned British anthropologist, is known for jotting down Goodhart’s Law. This law points out that individuals will steer their actions anticipating the effect they will have on an existing policy. Willful neglect happens when the systems in place of measuring the processes are being subverted for generating the semblance of performance, in other words by gaming the KPIs set out by management. It is most likely to happen when KPIs are too complex compared to the crude measuring tools used to track them. For example: Tickets within a service desk need to be handled within 2 days, but the measuring tools track the successful closing of a ticket in the ticketing system, resulting in tickets getting closed without being properly handled and a duplicate ticket being opened to still resolve it afterwards.

Technical Debt is a concept that is hard to understand for most organization, and even harder to measure and remedy. It tends to fall to the architect to make the management aware of the inherent dangers of letting technical debt (usually in the form of legacy applications) accrue to the point that it is severely hampering both you day-to-day operations and your ability to improve upon value-adding processes that are supported by these legacy components.

Dealing with technical debt can happen in three ways. The teams in your organization responsible for change (both in business and IT) constantly refactoring the debt away up to the point where it becomes virtually nonexistent, but still requiring eternal vigilance. You could opt for the sustainable approach where you don’t diminish legacy code as aggressively but aim to have all new capabilities to be developed in the new ways of working, rather than tacking on to existing legacy. A third way is to deal as little as possible with it. We take the ostrich approach and simply ignore the debt. We don’t do any major refactoring and let new development bog down, resulting in a compound growth of the debt.

| Continuous Refactoring | Sustainable Refactoring | Minimum Refactoring | |

| Debt acquisition | You eventually repay almost all debt. | You keep debt at the same level by paying off all the interest. | You do not repay debt and interest is added to the debt and debt grows exponentially. |

| Repayment Frequency | Develop features and refactor the new and old code heavily. | Develop features and refactor the new and old code a bit. | Only developing new features with little to no refactoring. |

| Debt Burndown Rate | Linear, going down. | Linear, constant. | Grows exponentially. |

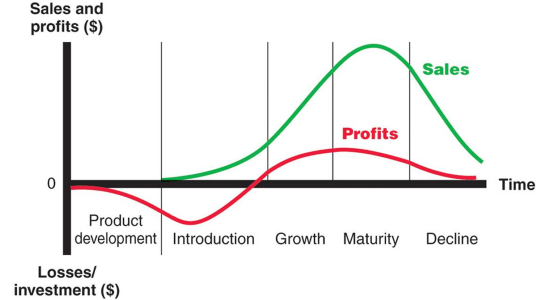

Intuitively, one might decide that the third option (compound growth) is never a viable tactic. However, when taking into account the standard product lifecycle, it might simply be that the legacy components only serve the operational processes of a product line for a product that is in decline, and in which an organization subsequently no longer wants to invest much. If a component is marked for a “natural” death, refactoring becomes less appetizing, and the funds needed to reduce technical debt can be better spent elsewhere.

Impact on Architectures

All of these disruptions can cause the need for existing architectures to be revisited. Depending on the realities of the organizations and the likelihood of the disruptions happening, a risk assessment and mitigation for when they do happen should be part of all architectural exercises. Whatever mitigation is added to the initiative will depend on the cost to mitigate mapped to the frequency and the impact of the risk, augmented with complementary factors, as laid out by the Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) risk assessment methodology. Options for risk mitigation can then include:

- Assume/Accept: The decision to accept the risk without making preparations for its possible occurrence.

- Avoid: The architecture is adapted to make sure this risk cannot happen by for example reducing the scope and removing the components that are sensitive to this type of risk, or adding implementations of safeguards.

- Control: Adapt the architecture to reduce the impact and likelihood of the risk.

- Transfer: Similar to “Accept”. The ownership and responsibility are shifted to someone willing to accept the risk.

- Watch/Monitor: Monitor the environment for changes related to this risk in order to be able to act very quickly should it occur.

| Thought | Enterprise Architecture | Business Architecture |