The book pits HTTP(S) against SOAP in the battle of protocols when implementing web services. Where SOAP only uses HTTP(S) as its transport channel, REST embraces all of the principles of the protocol. In order to assess why REST is such a good fit for service design, let’s review what a web service is all about. Web services are software components that are developed to expose business capabilities. To do so, they are comprised of the following elements (available through the provided contract):

- Operations: A set of exportable operation signatures that can be accessed by the consumer of the service.

- Document Schemas: A definition of the data types that can be exchanged with the service through the provided interfaces.

- Non-Functional Specifications:

- Conversation Specifics: Indication on how information can be exchanged with the services, such as request-response or fire-and-forget.

- Quality-of-Service Characteristics (QoS): Indicators for QoS characteristics such as availability, latency and throughput.

- Policy Specifics: Requirements specifications for how to interact with the service. These are stipulations on for example security and transactional contexts.

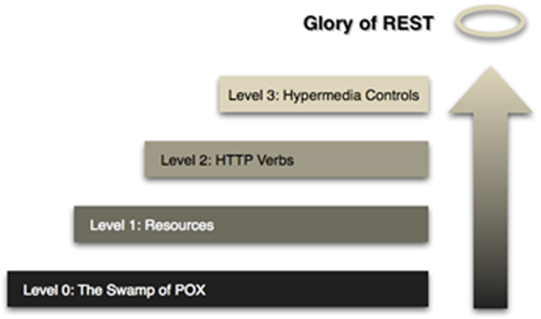

The first five chapters of the book deal mainly in building a transformative journey for an organization to shift to using REST services according to the Richardson’s maturity model. The model starts from a very basic implementation not following any of the REST standards up to a full implementation of services with the principle of “Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State” (HATEOS). The remaining chapters deal with how to address any non-functional specifications these services must cover. In these remaining chapters there is a brief intermezzo where the authors delve into the ATOM format as a substitute for transferring data and a means for event driven service design. As these chapters are a bit the odd ones out, this synopsis will not delve into them too deeply.

Richardson’s Maturity Model

Level 1: Resources

In order to clarify the success factors of the WWW as a platform for services on a global scale, the book sketches a high-level overview of the architecture behind it, and the salient points for the REST

architecture. Formalized by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the specification can be found here. Services are exposing resources through Uniform

Resource Identifiers (URI). Their relation is many-to-one: A resource can be identified by more than one URI, but any URI will only point to one resource, making it addressable and accessible for manipulation

via HTTP. This endpoint will follow a specific structure: <protocol>://<host>/<resource>/<identifier> with the identifier piece being optional. To fetch consultant Peter De Kinder from the service

would look something like this:

https://www.bestitpeople.com/consultant/peterdekinder

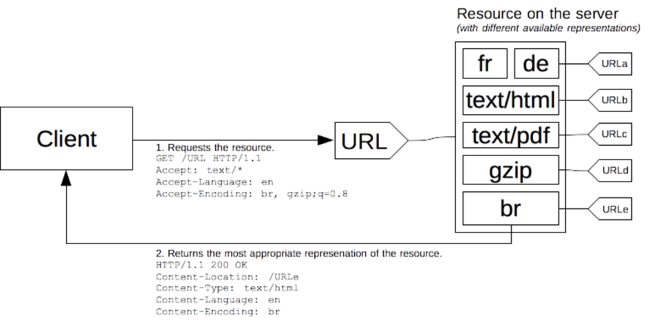

The Web does not differentiate between resource representations. Resources can thus have multiple representations. These representations are views encoded in a specific format (Json, XML, MP3…) to match the needs of the consumers through content negotiation (see further down). This consumer friendliness does not relinquish control on how to represent or modify these resources. This is still the purview of the services that control them. The encapsulation of the resources support isolation and allow for independent evolution of functionality in order to preserve loose coupling, one of the key aspects of the Web. One consideration to make is that you should name your resources in such a way that they are intuitive: They must indicate the intent of the service as well as already provide a rudimentary level of documentation.

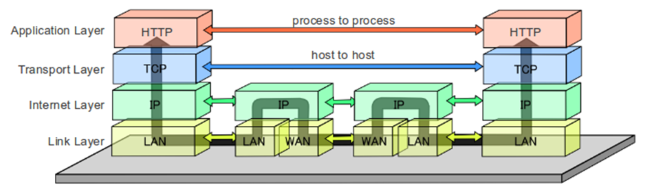

As stated earlier: HTTP is the spearpoint for this architecture, and this protocol stacks on top of the TCP/IP protocols and a series of WANs and LANs for its communication. These networks are hosted on a set of geographically widespread and commoditized web servers, proxies, web caches and Content Delivery Networks (CDN) that host the resources and manage traffic flow without intricate canonical data models or middleware solutions.

HTTP Protocol

Loose coupling in combination with the caching possibilities of the network allow for the needed scalability asked from services and application in today’s software development. But since the Web doesn’t try to incorporate QoS guaranties and other non-functional specifications, there is a need for fault tolerance in the services design, as the Web will always try to retrieve resources, even if they are nonexistent.

Level 2: HTTP Verbs

The manipulation through HTTP is done using the verbs that are supported in the protocol: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, OPTIONS, HEAD, TRACE, CONNECT and the somewhat newer PATCH. These verbs form a uniform interface with widely accepted semantics that cover almost all possible requirements for distributed systems. Add to this a set of response codes that can be returned together with a payload of which the most famous is the 404 – Not Found.

Combined with employing HTTP and URIs for this implementation, we are compliant with level two of Richardson’s maturity model. In addition to this we need a way of communicating and handling failures that might occur during the execution of a transaction. For example: If we take a standard ordering system where the transactions manipulate said order (our resource), we get the following contract:

| VERB | URI | STATUS | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| POST | /order | 201 | A new order is created, and the location header returns the new order’s URI. The complete order needs to be provided. |

| 409 | The creation of the order conflicts with the current state of another resource and is rejected. For example: The order being created already exists. | ||

| GET | /order/{id} | 200 | Returns the current state of the Order identified by the URI. |

| 404 | Returns a status code indicating the requested resource cannot be found by the service. | ||

| PUT | /order/{id} | 200/204 | Updates the Order identified by the URI with new information. Only a partial order is needed (with all fields that need to change). The difference between the 200 and 204 response is just aesthetic and depends on the choice of the organization. |

| 404 | Returns a status code indicating the requested resource cannot be found by the service. | ||

| 409 | The update has created a conflict with the current state of the order and is rejected. | ||

| 412 | The update is attempting to update a resource that has been modified since it was last fetched. This signals a concurrency issue. | ||

| DELETE | /order/{id} | 200/204 | Logically removes the order identified by the URI, and in the case of a 200 response, we could return the final state of the order. |

Some response statuses can be generated by all of the above HTTP verbs:

| STATUS | Description |

|---|---|

| 400 | A malformed request was sent to the service. |

| 401 | Unauthorized Access. The party trying to act in a transaction does not have the proper authorization to perform the requested actions. |

| 405 | Method not allowed. The execution of this verb is not allowed on the current resource type (in our case order). In case of a DELETE this could also mean that the resource is currently in a state that doesn’t allow it to be deleted. |

| 500 | Internal Server Error when the service is unavailable or internally crashing without possible recovery. |

When designing and implementing services we always need to consider whether calling these services should be safe and/or idempotent. Safe services have no server-side side effects that the consumer of the service can be held accountable for. These service calls will not trigger any effects that will change the state of resources. Idempotency is the fact that a service call can be done multiple times without yielding a different result in any of its calls. Each identical call will result in an identical response. The GET of a resource is a call that is considered both safe and idempotent. The service call will return the same result no matter how many times it is called, and it will not alter the state of the resource it is requesting.

| HTTP Verb | Safe | Idempotent |

|---|---|---|

| GET | x | x |

| POST | x | x |

| PUT | x | |

| DELETE | x | |

| PATCH |

Other verbs (all both safe and idempotent) that are commonly enabled on REST services are the following:

- HEAD: Returns only the HTTP headers of the request in order to determine the context of the resource.

- OPTIONS: Queries the endpoint for the possibilities it offers. This verb is typically also used by browsers as a preflight request to determine whether Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is allowed.

- TRACE: Allows for a loop-back test with debug information. This method is not included in default authorization checking, and should be disabled in production, as it can be a security risk.

The book concludes its elaboration on the second level of Richardson’s Maturity with an overview of some of the more popular technologies and frameworks and how they tackle the creation of a consumer for the services defined with REST. These are rather straightforward for those developers that routinely use them, so we will not go deeper into them.

Level 3: Hypermedia Controls

Hypermedia systems extend the resource state that is being manipulated by the services with additional characteristics. The resource state becomes a combination of:

- The values of the individual variables that make up the resource

- Links to related resources

- Links to manipulate the current resource (creating, updating, deleting…)

- Evaluation results of business rules encompassing the resource and other related resources

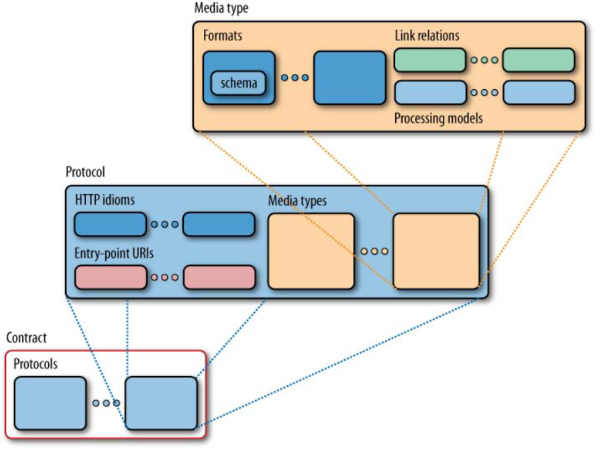

The links mentioned make up a domain application protocol (DAP) that advertises all possible interactions with the resource. The consumers of this service use these published interactions to discover how to interact with the resource. Hyperlinks are the weapon of choice when adding such links to interactions. A DAP also consists of two other key components: Media Types (as mentioned before), and HTTP Idioms (which make up the HTTP uniform interface: verbs, standard headers, error codes…). In short: Link relation values tell why the consumer should activate a hypermedia control by stating the role of the linked resource, the media type tells the consumer what it can expect as the response of a link, and the idioms manipulate the resources represented by the links.

The resource state can be in any format as REST’s hypermedia tenet does not force any set media type. IANA is the official registry of MIME media types and maintains a list of all the universally accepted MIME types. The resource should indicate in the Content-Type header of its responses the ideal way of interpreting it. Similarly, the Accept header is part of the HTTP spec for requests. In this header the consumer can indicate which media type it wishes to receive. Based on these two headers, a system of content negotiation is set up where the request of a consumer can be matched to the proper implementation to return the desired result and how it is conveyed.

The HTTP specification allows for the definition of custom media types as well. This is used to inform the consumer about the result to be expected in greater detail. Where “application/xml” informs the consumer

which format to expect, it doesn’t give any insight on which data to expect. This can be done by creating a custom media type in the vendor range (vnd). This type adheres to the format:

<media type>/vnd.<owner of custom media type>.<type of data>+<media suffix>

For example: If the return of a service would list the detail of a consultant for the company “Best IT People” in XML format, you would get the following media type: application/vnd.bestitpeople.consultant+xml.

Just beware not to create a set of customer media types that map directly onto the representation formats in the code of the service. That would create unnecessary tight coupling.

By utilizing the HTTP specs, URIs and hypermedia, REST allows for scalability, uniformity, performance, and encapsulation when designing a distributed system. These conventions guide the service design, and thus have an impact on how the service will be exposed to the outside world. This exposure is what we call the service contract. A service contract informs the consumers of the service about the format of the resource (media type), its processing model (protocol) and the links to related resources. The contract also shields the consumer from the implementation details, decreasing the coupling between the service and its consumers, and at the same time heightening security through obfuscation. This loose coupling is further enhanced by applying Postel’s Law: “Be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others”, also known as the robustness principle. An example of how to go about implementing this law, is the Tolerant Reader pattern.

Although the service contract has these conventions as a foundation to build upon, there is still a need for some thought to be put into the data modeling of the resources that will be exposed. The decisions on how to divvy up the data assets that make up the business context into exposable resources can be a daunting endeavor, and numerous design factors should be taken into account based on the context in which this services and their contract are designed.

However, there are some recurring factors influencing the size of the resource representation:

- Atomicity: Composite resources that share blocks of data can cause the other resource to enter an inconsistent state.

- Importance of the Information: The optionality of certain components could indicate them belonging to a separate resource representation.

- Performance and Scalability: the size of the resource and the frequency with which it is accessed, determines how long it takes for it to be passed over the network.

- Cacheability: This is greatly enhanced if none of the components of the resource changed at a different frequency from the others.

Designing the contract before implementing the service is what is called the contract-first approach. This approach might seem like a lot of design/thinking upfront, and it will require additional development when exposing legacy code as a service or implementing retrofits, but despite this additional preparatory work, it does grant several benefits:

- Implementation teams that will make use of the service can work in parallel with the service development team.

- The contract is known before starting development so all teams have an idea of what to expect from the service. This can give a healthy discussion between provider and consumer teams on how to tweak the service an get ahead of mismatches in expectations.

- An existing contract allows for code generation of stubs and proxies of the service to test for connectivity and availability of the service that will be developed.

- Contract-first helps with keeping the contract and the underlying implementation loosely coupled as the contract is not based on the code that is run.

There are concepts that I like from this level, such as the use of vendor-specific media types and contract-first design, but mostly this level carries with it a lot of added complexity for a return that only becomes tangible when working with experienced development teams and an organization with sufficient maturity in the field of service design. This is the main reason that level 2 services are the most common. And nothing stops us from cherry picking these concepts and applying them to our level 2 services.

Non-Functional Characteristics

There are several considerations that weigh on the design and implementation of services that are of a more technical nature. Some of them have already been mentioned, but there is a selection of these characteristics that are worked out in the book, each with its proper impact on the scalability of the services.

Caching

Caching can be done at numerous points along the request/response chain of a service call. When a resource is requested, and one of the intermediate components has a version of this resource, they will provide it back. Otherwise the service call will reach the origin service and collect the real-time data. The origin service should provide the intermediate components the rules for when and how to cache as well as how long the data would be considered “fresh”. Evidently, the closer the caching component is to the consumer in the request/response chain, the less expensive (reduction of bandwidth and of load on the origin service) the call. The other benefits of caching are a reduced latency (a quicker roundtrip time) and a reduced impact of possible network failures.

While there are benefits to caching, there are also reasons not to do so. In these situations, caching will harm more than it benefits, or might simply not be allowed:

- If the GET of the resource generates side effects from being accessed (for example a counter system that limits how many times the resource may be requested by consumers or some early bird system that benefits the first so many consumers), the cache would prevent these side effects.

- When the system in place doesn’t tolerate any latency in data to be retrieved and we need to be sure that the data received is real-time (for example a heart monitor in ICU wards).

- When caching is not allowed for regulatory reasons or security/privacy risks.

- When the frequency with which the data changes is so high and the period that the data is not stale is so small that caching would never trigger.

Aside from all the caching that can be added on an applicative level, there are already several components capable of caching that are native to the infrastructure of the web:

- Local Cache: A store of cached representations from many origin servers at the behest of a single consumer, either in memory or persisted.

- Proxy Cache: A server that stores representations from many origin servers to many different consumers. This component can reside either outside or inside the corporate firewall.

- Reverse Proxy: A component that is a type of proxy server that retrieves resources from a single origin server on behalf of any number of consumers. It focuses mainly on load balancing, HTTP acceleration and security features.

The caching components are instructed on how to handle the caching of the resources they hold by using these specific HTTP response headers:

- Expires: Indicates the length of the period the cached resource can be used before being considered stale.

- Cache-Control: This header can also be provided by the consumer of the service in the request. It allows for a set of comma-separated directives on how to handle the caching of the resource:

- Request-only directives:

- max-stale[=<seconds>]: Indicates the client will accept a stale response. An optional value in seconds indicates the upper limit of staleness the client will accept.

- min-fresh=<seconds>: Indicates the client wants a response that will still be fresh for at least the specified number of seconds.

- only-if-cached: The cache should either respond using a stored response, or respond with a 504 status code if no cached version of the resource is available.

- Response-only directives:

- must-revalidate: Indicates that once a resource becomes stale, caches must not use their stale copy without successful validation on the origin server.

- public: The response may be stored by any cache, even if the response is normally non-cacheable.

- private: The response may be stored only by a browser's cache, even if the response is normally non-cacheable.

- proxy-revalidate: Like must-revalidate, but only for shared caches. Ignored by private caches.

- s-maxage=<seconds>: Overrides max-age or the Expires header, but only for shared caches (e.g., proxies). Ignored by private caches.

- Generic directives:

- max-age=<seconds>: The maximum amount of time a resource is considered fresh. Unlike Expires, this directive is relative to the time of the request.

- no-cache: The response may be stored by any cache, even if the response is normally non-cacheable. However, the stored response MUST always go through validation with the origin server first before using it

- no-transform: An intermediate cache or proxy cannot edit the response body, Content-Encoding, Content-Range, or Content-Type.

- no-store: The response may not be stored in any cache. Note that this will not prevent a valid pre-existing cached response being returned.

- Extended directives (not part of the official HTTP standard, but universally used):

- Immutable: Indicates that the response body will not change over time.

- stale-while-revalidate=

: Indicates the client will accept a stale response, while asynchronously checking in the background for a fresh one. The seconds value indicates how long the client will accept a stale response. - stale-if-error=

: Indicates the client will accept a stale response if the check for a fresh one fails. The seconds value indicates how long the client will accept the stale response after the initial expiration.

- Request-only directives:

- ETag: An opaque string token that is associated with the resource to verify its state. This can be used to determine whether or not a resource has changed since the last time it was requested. Therefor this will also be used in concurrency tests.

- Last-Modified: The date at which the resource was modified the last time before this request.

Consistency

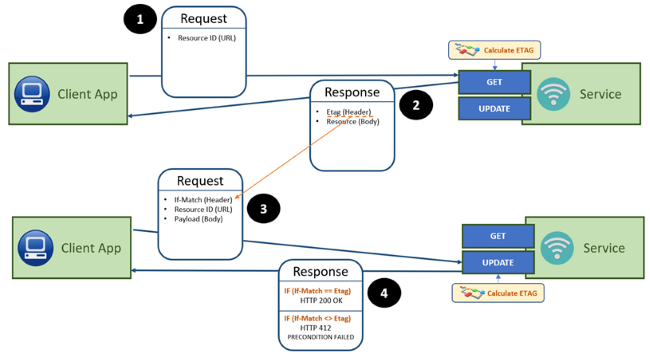

It is important that data is kept consistent across various manipulations, especially when it is being exposed to and manipulated by the consumers of stateless services. One of the key risks that threaten this consistency is concurrent writes to the same resource. The scenario is straightforward. Consumer A reads the current resource. Consumer B reads the same resource. Consumer B updates the resource, followed by consumer A updating the resource. In this scenario, consumer A never saw the changes that consumer B made, and more than likely erases them by updating the resource.

One way to tackle this scenario is to introduce conditional updates. The idea is that when a consumer reads a certain resource, it gets passed a unique representation of this resource in the “Etag”-header (for example a MD5-hash of the non-transient fields of the resource). Each time any consumer is updating a resource, the consumer needs to provide this value in the “If-Match”-header. The idea is that when the update is processed by the service, it checks whether the content of the header still matches the representation of the resource. If it is still the same, it will update the resource and return the result (HTTP 200 OK status). If between the read and update of the resource by this consumer, another consumer modified the resource, the representation value will have changed, and the update is denied (HTTP 412 PRECONDITION FAILED status). It is then up to the consumer to fetch an up to date resource and decide whether or not still to process its changes. The “If-None-Match”-header checks whether a resource exists with the representation, and if not, proceed with the update. This could be used to prevent the creation of duplicate resources in the database.

There are also headers based on the modification date of a resource for indicating to the service that it should behave in a conditional way. Personally, I feel that this adds the additional complication of syncing the date between the service and its consumers, and that using the ETag is more resilient:

- The “If-Modified-Since” header only executes when the resource has been modified since the given date. This header works with the last-modified header instead of the ETag.

- The “If-Unmodified-Since” header is the inverse of the “If-Modified-Since” header.

Security

There is an entire chapter dedicated to security in the book. However, since this is one of those areas of expertise that has rapid evolutions, the contents of this book (written in 2015) are somewhat dated. It evaluates authentication and authorization mechanisms based on four characteristics associated with secure distributed systems: Confidentiality (how well data can be kept private), Integrity (how to prevent unlawful changes to data), Identity (how to identify parties involved in the transactions) and Trust (what to allow the previously mentioned parties in transactions).

The book offers up the following mechanisms to achieve these characteristics:

- Basic Authentication: A very straightforward username/password combination passed along as a base64-encoded string in the request by using the Authorization header. Too easily intercepted and decoded to be useful in production systems.

- Digest Authentication: A challenge/response exchange that happens in reaction to sending a request. The initial request is resent with additional information stored in the various security headers (qop, nonce, opaque, username, uri, nc, cnonce, response). This mechanism is safer than Basic Authentication, but still falls prey to man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Transport-Level Encryption: This application of HTTPS for service exchange remains up till today a gold standard in security. One caveat is that this does not affect the payload, so this payload is still vulnerable at the termination point of the HTTPS connection. HTTPS is more expensive than HTTP in terms of performance, and does hamper caching in the network components, most of the time this tradeoff is warranted.

- OpenID and OAuth: Since the book describes version 1 of Oauth, this part of the book is outdated, and is only of interest as a historical perspective. For an elaboration on OAUTH2, see my previous thought on the topic.

Web Semantics

There is a chapter dedicated to Web Semantics. This concept can be characterized as the meaning behind data and information, and stems from a need to make sure that all parties involved in the management of a resource have the same interpretation for it. This shared interpretation is then formalized in a contract (using frameworks such as OWL or RDF), making the resource meaningful for both people and consuming services. It mostly deals with the difference between data, information and knowledge in terms of structure (relationship between different information pieces that make up a resource) and representation (in which format to expose it).

Web Semantics was very popular for a time, but as I have described in a previous thought, for me it no longer bears much relevance. That being said, remnants of the technologies can still be found in for example the twitter card headers used to aptly represent website links on the twitter feed. These metatags use RDF as their foundation.

Conclusion

The WS-* protocol stack might still be considered more developed, but this comes with an increased complexity that hinders its uses. It still has some legacy that it cannot shed, such as for example the disregard of encapsulation in exposing its internal workings via the WSDL. But it does come with several strong points to cover the non-functional needs of service design. Not in the least its security features that come with a full suite of cryptographic techniques provides an end-to-end mechanism or transferring information. And we cannot forget that at this time its adoption by organizations is still very widespread.

However, REST has gained substantial maturity on these topics as evidenced by this book and has since become the new favorite. REST isn’t a perfect fit for every situation, as no solution ever is. And its distributed nature does necessitate strict monitoring of performance and other metrics such as mean time between failures. But the familiarity with the World Wide Web architecture carries enough weight to add an intuitive aspect to its development and use.

| Review | SOA |