It's the Law!

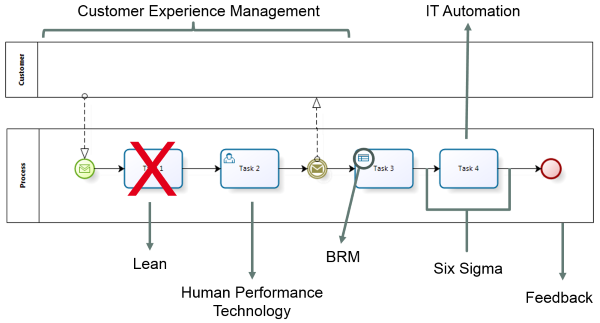

24th of December 2015One of the key concepts of Business Process Management is the continuous improvement of the business processes. These improvements can be done in many ways, as illustrated by the many different techniques that have popped up since the dawn of BPM. Think of Six Sigma, Lean, Hammer’s BPR and so on. Each of these techniques acts on the process in a different way, focusing on what they view as the critical components of a process.

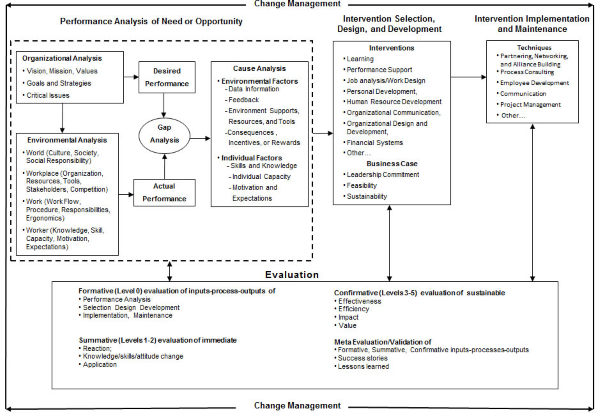

One of these techniques is Human Performance Technology. This technique is a holistic approach to attaining desired accomplishments from human performers by determining gaps in performance and designing cost-effective and efficient interventions. This methodology was pioneered by Tom Gilbert and originally determined the causes of these gaps into six categories of which there is a lack:

- Consequences, incentives and rewards

- Data, information and feedback

- Environmental support, resources and tools

- Individual capacity

- Motives and expectations

- Skills and knowledge

Later on (as shown in the diagram below) a model for improving the performance was devised, based on resolving these gap. The gap categories were expanded, as well as personalized by other authors for their proper methodologies. And different nuances were also introduced into the equation based on the different types of stakeholders: Customers, suppliers or employees. To close these gaps, the appropriate measures need to be determined to address these causes. HPT attacks this issue with a phased approach:

- Analysis: The specific tasks to be performed are identified, as well as to what extent there needs to be training or another type of performance support the job necessitates. Traditionally this is done through a survey of the performers or through a facilitated panel of experts. The results enable the trainers to select the tasks appropriate for training as well as the proper training methods.

- Design: The specific learning objectives (or performance objectives) are developed. Linked to these objectives is a hierarchy of different levels and types of learning (such as stated by Robert Gagne). The relevance of these types and levels is what we elaborate on. The idea is to deliver the training in such a way that these types of learning (lectures, discussion, hand-on exercises…) are supported.

- Development: We develop the training based on the objectives and the types of learning that were decided upon. This comes down to writing out the training, producing the teaching aids, etc.

- Implementation: Once the development of the training has been finalized, the trainings need to be given to the target audience.

- Evaluation: The effectiveness of the training is measured using the levels of learning evaluation pioneered by Donald L. Kirkpatrick and elaborated by several others.

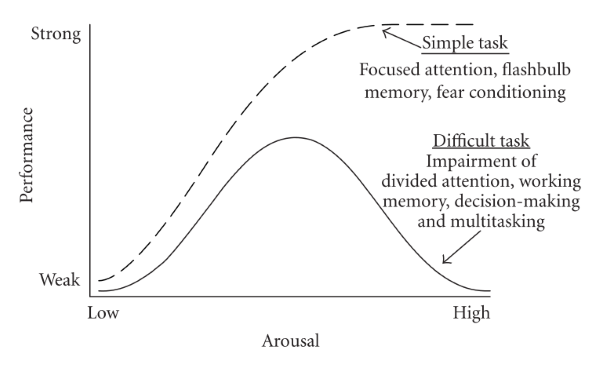

But this is just serving as an introduction to the actual theme of this though, namely the Yerkes-Dodson Law of Arousal. This law could either be used for charting the gap of incentives or for the motives and expectations of employees. The Yerkes-Dodson Law suggests that there is a relationship between performance and arousal. Increased arousal can help improve performance, but only up to a certain point. There is a level at which performance enhancement peaks, and if further stimulated, performance starts to diminish again.

The law noted down in 1908 by psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson. They ran an experiment in which they observed that mild electrical shocks could be used to motivate rats to complete a maze, but when the electrical shocks became too strong, the rats would counterproductively scatter about in random directions, trying to escape. This behaviour was then plotted into a graph, as shown below. This is the original graph that came out of the experiment.

We see here that even though incentives for complex tasks seem to top off at some point, for simple tasks the dip in performance doesn’t seem to happen. Or at least at lot less a lot later. To project this onto HPT, this indicates that incentives (such as bonuses, increased pay and the sorts) only seem to work for those simpler (often mechanical) tasks which are quickly going out of fashion in companies and industries around the globe, as we move to more and more knowledge work. This is certainly a caveat towards employers how in general still rely heavily upon these extrinsic incentives. They only work up to a certain level, and this level is notoriously difficult to pinpoint without harming the desired performance of your employees.

I am not the first to bark up this particular tree. While writing this thought, I am reminded of a TED Talk back in 2009, where Dan Pink, former speech writer to Al Gore, explains this phenomenon by illustrating it with some more recent social and psychological studies that seem to concur with the findings of Yerkes and Dodson. Or as he states it: There is a mismatch between what science knows and what management does.

| Thought | BPM |